Introduction

Two recent proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would erode the principal source of revenue for local governments — property taxes — and worsen existing economic and racial inequities. The senior property tax freeze proposals come in the form of an initiative petition for the 2024 ballot (IP 10) and a legislative resolution (Senate Joint Resolution 202) in the 2024 legislative session.[1] The proposals are structured in a way that guarantees that the revenue loss grows over time. As a result, they will eat away at the ability of local governments to pay for libraries, public safety, and many other local services, while also reducing funding for K-12 schools. The proposals would also worsen economic and racial inequality, as they would disproportionately benefit the non-poor over those living in poverty, and disproportionately benefit white Oregonians over Oregonians of color. While claiming to be a response to housing unaffordability, the proposals exclude those Oregonians most likely to be burdened by housing costs: renters. In short, to the detriment of Oregonians, freezing senior property taxes would erode local services and worsen existing inequities.

Two recent proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would erode the principal source of revenue for local governments — property taxes — and worsen existing economic and racial inequities. The senior property tax freeze proposals come in the form of an initiative petition for the 2024 ballot (IP 10) and a legislative resolution (Senate Joint Resolution 202) in the 2024 legislative session.[1] The proposals are structured in a way that guarantees that the revenue loss grows over time. As a result, they will eat away at the ability of local governments to pay for libraries, public safety, and many other local services, while also reducing funding for K-12 schools. The proposals would also worsen economic and racial inequality, as they would disproportionately benefit the non-poor over those living in poverty, and disproportionately benefit white Oregonians over Oregonians of color. While claiming to be a response to housing unaffordability, the proposals exclude those Oregonians most likely to be burdened by housing costs: renters. In short, to the detriment of Oregonians, freezing senior property taxes would erode local services and worsen existing inequities.

Summary of proposals to freeze property taxes of seniors

Both IP 10 and SJR 202 create a new property tax break for homes owned by seniors. To determine how much a homeowner owes in property taxes, a taxing district applies a tax rate to the home’s “assessed value.” Both proposals lock in the “assessed value” of the home for eligible properties. A property is eligible for the property tax freeze “when at least one person is 65 years of age or older on or before April 15 immediately preceding the beginning of the property tax year and, either individually or jointly, owns and occupies the home as their primary residence.”[2]

Eligibility is only the first step; the second is to enroll the property with the county of residence. If one of the proposed property tax freezes for seniors is approved by Oregonians in November of 2024, each county will need to develop a process for people to enroll.[3] Doing this in a way that is accurate, consistent, and simple will require significant work by county staff and may take months to implement. Given that, it’s likely people will not be able to enroll until 2025 and will not see property tax values frozen until the 2025-2026 property tax year at the earliest. It is the year after enrollment when property tax benefits accrue to enrolled properties.[4]

For eligible properties enrolled with the county, the tax freeze remains in place until the property is no longer owned, individually or jointly, or occupied as the primary residence by someone 65 years of age or older. That means the freeze ends when the owner who is a senior dies or moves to another primary residence. The freeze proposals also provide that the assessed value of the home is to be reset to what it would have been in the absence of the freeze upon the sale or transfer of the property, or if certain improvements are made to the property.[5]

Senior property tax freezes are a revenue gash that will worsen in time

Although it is difficult to put precise numbers on it, the revenue loss that would ensue from the enactment of either of the proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would grow over time due to two factors: the structure of the policy itself and the aging of the population. As such, over time, it would eat away at the main source of revenue for cities, counties, school districts, library districts, fire districts, and more.

Property taxes are a vital source of revenue for school districts and local governments in Oregon. Public services such as libraries, public safety, fire departments, and more are largely funded by property taxes. To provide a sense of the importance of property taxes to local governments, consider the following examples: property taxes make up 60 percent of Multnomah County’s discretionary budget and 70 percent of Baker County’s general fund annual revenue.[6] Although property taxes no longer constitute the principal source of funding for K-12 schools, they nevertheless remain an important resource. About one-third of the funding for schools comes from local sources, primarily property taxes.[7]

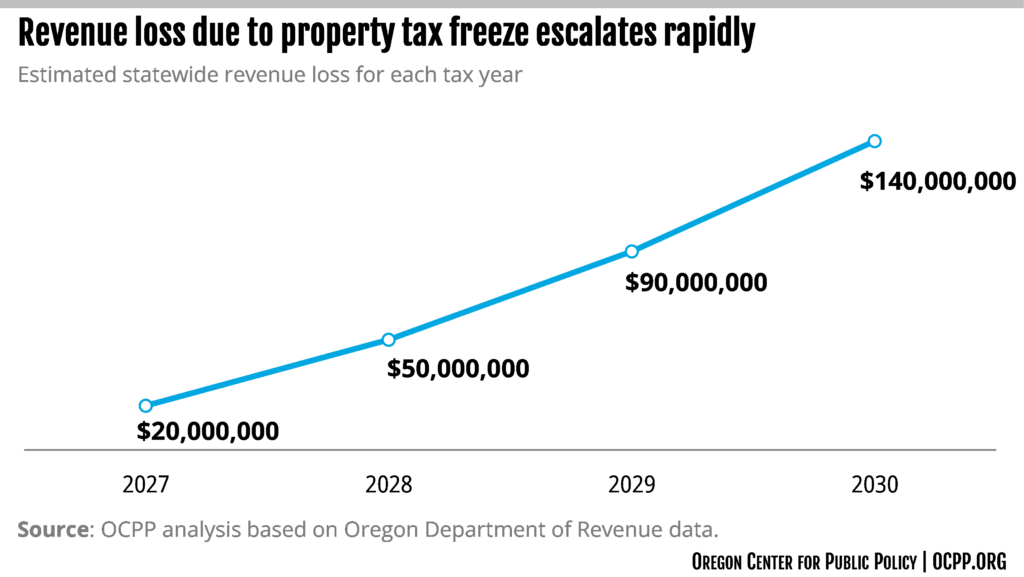

It is difficult to arrive at a precise revenue estimate based on publicly available tax data, but a conservative estimate of the cost of either of the proposed property tax freezes in the first year after taking effect (tax year 2026-27) is that the combined loss among all local taxing districts in Oregon would be more than $20 million.[8] The following year (tax year 2027-28), the statewide loss would escalate rapidly to more than $50 million. By the end of the decade, the annual revenue loss from a property tax freeze for seniors would approach $140 million. To reiterate, this is a conservative estimate. Appendix A explains the methodology used in this calculation.

The structure of the measure guarantees that the revenue losses will grow over time. In 1997, the enactment of Measure 50 severed the basis of property taxes from the traditional real market value to an “assessed value” that, generally speaking, may not grow by more than 3 percent per year. Except in the year Measure 50 took effect, the statewide total of assessed value has increased each year.[9] A property tax freeze for seniors locks in the current assessed value for eligible homeowners until the property no longer qualifies because the homeowner who is 65 or older dies or no longer resides in the home, the house is sold, or certain factors trigger a reassessment of the property. Until one of those events happens, the assessed value remains frozen at the level when the homeowner first enrolled the property in the program administering the property tax freeze. And every year of eligibility, the difference between the assessed value under Measure 50 and the frozen level under the tax freeze grows, increasing the property tax loss to the local taxing jurisdiction.

Demographic changes will exacerbate the revenue loss — an aggravating factor not reflected in the revenue estimates above. Like the country as a whole, Oregon’s population is aging. The share of Oregon’s population 65 and older is projected to rise from 18.6 percent in 2021 to 24.2 percent by 2050.[10] By 2050, seniors are projected to account for more than 40 percent of the population of some Oregon counties, including Curry, Grant, and Wheeler. As the share of the population 65 and older increases, so too does the number of Oregonians potentially eligible for the property tax freeze as well as the loss of revenue to pay for local services.

Property tax freezes for seniors are inequitable, cutting taxes for many who don’t need help while excluding many who do

The two proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors are inequitable on several levels, as they would confer tax benefits on many well-off homeowners while offering no help to renters struggling to keep a roof over their heads. They would also further exacerbate income and racial disparities.

Proposals exclude renters, who are more likely to be housing insecure

Oregon’s housing crisis is especially severe for renters, and yet the proposed senior property tax freezes exclude them and their landlords from any benefit. Renters tend to have lower incomes than homeowners, and housing costs weigh more heavily on renters than homeowners. Households are considered to be “cost burdened” when they spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing.[11] In 2021, 61 percent of renter households in Oregon that included a senior were cost-burdened in terms of housing.[12] That was more than twice the rate of home-owning households that included a senior. Although the stated rationale for these policies is framed in terms of housing affordability for seniors on fixed incomes, the petition leaves out a large swath of seniors struggling to keep a roof over their heads because, by definition, they exclude renters.

Additionally, these proposals would further tilt the tax code in favor of homeowners over renters. Both the federal tax code and the Oregon tax code provide significant tax benefits to homeowners, including the ability to deduct interest on a mortgage and property taxes.[13] In the 2023-25 biennium, Oregon will spend about $915 million on the mortgage interest deduction and another $662 million on the property tax deduction.[14] These subsidies exclusively for homeowners are some of the largest tax breaks contained in the state tax code.

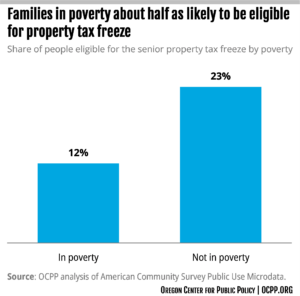

A property tax freeze helps the non-poor more than the poor

Oregonians living below the poverty line are much less likely to benefit from the proposed senior property tax freezes than people living above it. Specifically, about 12 percent of Oregonians in poverty would be eligible for the property tax freeze, compared to 23 percent of Oregonians not in poverty.[15] In other words, people living in poverty are about half as likely to benefit as people who do not live in poverty. Oregonians living in poverty are likely to be younger and are less likely to own a home.[16] For a policy claiming to help seniors avoid “being forced out of their home due to large yearly property tax increases,” the fact that it helps people in poverty less than those not in poverty shows it is poorly designed.

Proposals worsen racial economic inequality

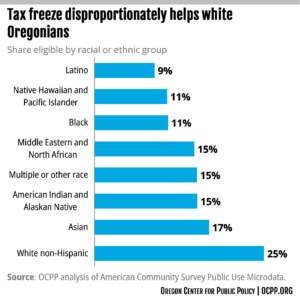

The proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors disproportionately favor white Oregonians, thereby worsening long-standing economic inequality by race. Black and brown Oregonians are significantly less likely to own a home than white Oregonians.[17] This is the result of a long history of racist policies and practices, such as federal housing policies in the mid-20th century that subsidized homeownership for white Americans, while denying the same benefits to people of color, and practices by the banking industry that steered Black and Latino homebuyers into risky subprime loans in the run-up to the Great Recession.[18] Not only are Black and brown Oregonians less likely to own a home, but they also tend to have lower incomes and lower levels of wealth, and are more likely to be housing insecure.[19]

Freezing the property taxes of seniors would heighten these inequities, as it creates a tax break that disproportionately favors white Oregonians. About 25 percent of white Oregonians would benefit, compared to 11 percent of Black Oregonians, 9 percent of Latino Oregonians, and 15 percent of Indigenous Oregonians.[20] This means white Oregonians are more than twice as likely to benefit as Black or Latino Oregonians from this tax break.

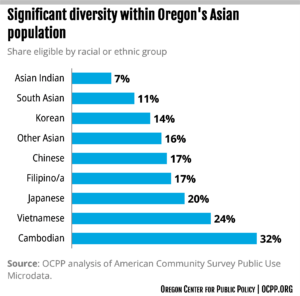

The racial and ethnic categories analyzed above blur some of the significant disparities that exist within racial and ethnic groups. When disaggregated into countries of origin, Asian Oregonians have one of the highest and some of the lowest rates of eligibility. Cambodian Oregonians rank around the top, with 32 percent expected to be eligible for the senior property tax freeze, statistically insignificant from Western European Oregonians.[21] On the other hand, South Asian and Asian Indian Oregonians are near the bottom, with only 11 percent and 7 percent expected to be eligible. Other groups, such as Vietnamese and Japanese are in the top half, while groups like Chinese and Korean rank much lower.

Freezing property taxes for seniors would worsen the horizontal inequity in Oregon’s property tax system

The proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would worsen the problem of horizontal inequity that already plagues Oregon’s property tax system. It is a basic principle of tax fairness that the tax system should treat similarly situated people the same. In the context of the property tax, this means that two properties worth the same should be taxed equally. Oregon’s property tax system already fails this test of fairness, and these proposals would make matters worse.

The existing horizontal inequities arise out of Measure 50. It severed property tax rates from real market value, tying the property’s assessed value — the basis for determining property taxes — to the real market value of the property as it stood in 1996 (minus a 10 percent discount). Since the enactment of Measure 50 in 1997, the assessed value of a property, generally speaking, has risen by no more than 3 percent, even if the real market value of the property has gone up more than that. Inevitably, this has resulted in homes that today have equal market value paying different property tax rates, or even more expensive homes paying lower property tax rates than less expensive homes.[22]

Proposals to freeze seniors’ property taxes would create yet another layer of horizontal inequity. By freezing property taxes for some homeowners, it would lead to more situations where owners of homes with the same or even higher real market value pay a lower property tax rate than an owner of a home with the same or lower real market value, while residents of both homes receive the same benefits from their local sidewalks, libraries, and health departments.

Conclusion

If enacted, a property tax freeze for seniors would erode funding for local services and worsen existing inequities. Freezing property taxes for homes owned by seniors would shrink the main source of revenue that local governments use to pay for services such as libraries, public safety, and fire departments. It would also weaken funding for K-12 schools, as property taxes remain an important source of funding for public education. At the same time, it would provide no benefit to those seniors who are most likely to struggle to afford housing: those who rent. Finally, the proposals to freeze property taxes for seniors would disproportionately benefit the non-poor over those living in poverty, and disproportionately benefit white Oregonians over Oregonians of color, exacerbating racial inequities.

Appendix A: Methodology

Two different datasets are used in this analysis. First, Oregon Department of Revenue (DOR) Property Tax Statistics reports are used to derive the revenue estimate. Second, the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Public Use Microdata sample are used for the geographic, demographic, and income analyses.

Revenue estimate

The revenue estimate is derived by first taking data from DOR reports for the 2017-2018 through 2022-2023 property tax years for each county. The residential property assessed values are taken for each county and then forecast into the future using the 2018-2023 value growth for each county, capped at 3 percent to align with the constitutional restrictions for existing properties. These forecasted assessed values are then reduced by taking the household eligibility estimate for each county to estimate the assessed value of properties eligible for the property tax freeze in each jurisdiction.

The difference between the 25-26 and the 26-27 tax year estimates, and then the difference for each subsequent year, is the projected loss of assessed value. This assessed value loss is then multiplied by the effective tax rate for each county in 22-23, as provided by DOR, to calculate the lost revenue in those property tax years. No effective tax rate was available for nine counties so the statewide average was used.

Since this forecast has to make an array of assumptions, and is several years away from now, it should be interpreted with caution. For example, this analysis assumes the percentage of the population eligible does not grow, which makes the estimates conservative, given the projected growth in Oregonians over 65 in the coming years. Another assumption is that no one changes their housing arrangement to maximize tax savings, such as by having an eligible family member move into their home and add them to the deed, which would allow them to take advantage of this tax break. The analysis also assumes that 60 percent of eligible Oregonians enroll in the first year and enrollment grows by 10 percentage points per year until plateauing around 90 percent in the 2029-2030 tax year. A higher enrollment rate, more tax-incentivized housing changes, and other conditions could significantly heighten the revenue loss.

Demographic analysis

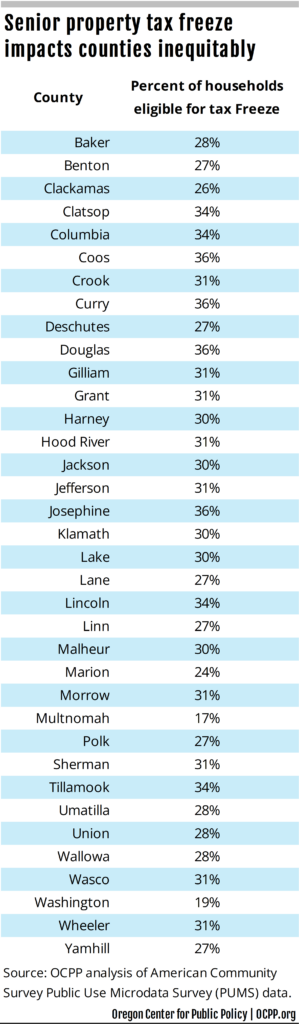

Analyses of geography, income, and racial and ethnic identity were built on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Survey for 2017-2021. This data includes detailed information on tens of thousands of Oregonians, including their age and if they are a homeowner or not, which enables this analysis to estimate if someone is or is not eligible for the senior property tax freeze. Using this binary variable of eligible or not, it’s straightforward to make weighted estimates of eligibility based on poverty status, detailed racial and ethnic identity, and Public Use Microdata Area (PUMA). The PUMA data is then apportioned to their respective counties using Geocorr (geographic correspondence engine) crosswalk files developed by the Missouri Census Data Center.[23] County estimates are listed in Appendix B.

Appendix B: County data

Endnotes

[1] Initiative Petition 10 (2024), Section 11m. (1) and Senate Joint Resolution 202, Oregon 2024 legislative session..

[2] Initiative Petition 10 (2024), Section 11m. (1).

[3] Initiative Petition 10 (2024), Section 11m. (7).

[4] Initiative Petition 10 (2024), Section 11m. (7).

[5] Reasons for reassessment of value included in the measure come from Article XI, Section 11(1)(c) of the Oregon Constitution. These include that property is new or has new improvements, partitioned or subdivided, rezoned, and a handful of other conditions.

[6] Multnomah County 2022-2023 adopted budget, Baker County 2022-2023 adopted general fund budget.

[7] Oregon Legislative Policy and Research Office, K-12 Education Funding, August 31, 2023.

[8] Given the uncertainty around the timing of each county creating their own enrollment program, and the start of 2026-2027 landing on July 1, 2026, we assume that’s the first year for full implementation. It is possible some counties launch programs that end up applying to the 2025-2026 property tax year.

[9] Oregon Legislative Revenue Office, 2023 Oregon Public Finance: Basic Facts, Research Report #1-23, February 20, 2023, p. D6.

[10] Legislative Policy and Research Office, Older Oregonians, October 27, 2023.

[11] Legislative Policy and Research Office, Older Oregonians.

[12] Legislative Policy and Research Office, Older Oregonians.

[13] Tom Cusack, First Ever Breakout of $1.4+ Billion in Oregon State Tax Breaks for Housing: Home Owners Get 91% of State Housing Tax Breaks, Oregon Housing Blog, July 7, 2008.

[14] Oregon Department of Revenue, 2023-25 Tax Expenditure Report.

[15] OCPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017-2021 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata sample. The difference between these two groups is statistically significant.

[16] OCPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017-2021 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata sample. People aged 65 or older have a statistically significantly lower poverty rate than people aged under 65. Similarly, people in poverty have a lower homeownership rate than people who are not in poverty, again with statistical significance.

[17] Oregon Center for Public Policy, Data for the People: Homeownership by Race.

[18] See Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (Liverlight: 2017); David Reiss, The Federal Housing Administration and African-American Homeownership, Journal of Affordable Housing, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2017. Jonathan Kaplan and Andrew Valls, Housing Discrimination as a Basis for Black Reparations, Public Affairs Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3, July 2007, at 261-63; Tracy Jan, “Redlining was banned 50 years ago. It’s still hurting minorities today.” The Washington Post, March 28, 2018; Dee Lane, “Major lenders aid decline of NE Portland,” The Oregonian, September 10, 1990; Kai Wright, “Wells Fargo Settles for $175M Over Steering Blacks and Latinos to Subprime Loans,” Colorlines, July 12, 2012; “OCPP Finds Racial Pattern in Oregon’s Subprime Lending,” Oregon Center for Public Policy, January 31, 2008.

[19] Guy Tauer, A Closer Look at Oregon’s Median Household Income, Oregon Employment Department, June 1, 2023; Oregon Center for Public Policy, Wealth Inequality in Oregon Is Extreme, November 3, 2022, available at; Oregon Center for Public Policy, Data for the People: Cost Burdened by Race.

[20] OCPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017-2021 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata sample. All racial and ethnic groups are statistically significantly different from white Non-Hispanic and statewide totals.

[21] OCPP analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s 2017-2021 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata sample.

[22] Ellion Njus, Tax breaks for gentrifiers: How a 1990s property tax revolt has skewed the Portland-area tax burden, The Oregonian, September 11, 2015.