In its current form, Oregon’s unusual kicker tax rebate deepens existing racial economic inequality.[1] Because of past and present forms of discrimination, Oregonians of color tend to have lower incomes and less wealth. The kicker makes matters worse, delivering to Oregonians of color a disproportionately smaller share of kicker dollars.

But most white Oregonians also don’t fare well under the current policy. That is because it is a relatively small group — rich, mostly white Oregonians — who are the primary beneficiaries of the kicker.

There are ways to reform the kicker that would produce more equitable results — reforms that would be good for Black, brown, and white Oregonians.

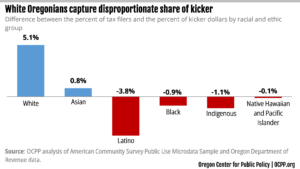

Communities of color get a disproportionately smaller share of kicker dollars, reinforcing economic inequality by race

The kicker is a tax rebate triggered when revenue collections come in 2 percent or more above what state economists predicted two years earlier. When that occurs, the entire unanticipated amount — not just the amount above the 2 percent threshold — goes back in the form of a tax rebate. As state economists explain, the kicker “does not mean Oregonians overpaid their taxes, it means our office underestimated revenues.”[2] Presently, the size of the rebate depends on the amount of taxes paid.

Most communities of color receive a disproportionately smaller share of kicker dollars relative to their share of Oregon’s income tax filers.[3] For instance, Latino Oregonians make up about 10.1 percent of Oregon tax filers, yet they collectively receive an estimated 6.2 percent of kicker dollars. Similarly, Black Oregonians and Oregonians who are American Indian and Alaskan Native (noted as Indigenous in charts) account for about 2.4 percent and 2.8 percent, respectively, of all Oregon tax filers, yet they receive an estimated 1.5 percent and 1.7 percent of kicker dollars.[4]

Those differences translate into smaller kicker rebates for the average Black and brown Oregonian. It’s important to note that the available demographic data does not allow for an estimate of the median (typical) kicker by race, only the mean (average). The mean is skewed upward since a significant portion of the kicker goes to the rich.[5] Indeed, in the kicker triggered in 2021, the mean kicker was $850, while the median was $420.[6] Nevertheless, the average itself reveals wide racial disparities. In the 2021 kicker, the average white tax filer got a rebate worth $909, compared to $542 for Black, $519 for Latino, and $512 for American Indian and Alaska Native tax filers.

Thus, in its current form, the kicker reinforces and deepens the existing, inequitable economic reality. Oregonians who are Black, Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native already tend to have lower incomes and levels of wealth compared to white Oregonians. This is the result of a long history of economic exclusion and exploitation.[7] The current form of the kicker reinforces this inequity by delivering smaller tax rebates to Black and brown Oregonians collectively — a group that is already more likely than white Oregonians to live paycheck-to-paycheck.[8]

Rich, white Oregonians are the main beneficiaries of the kicker

The main beneficiaries of the current kicker policy are the rich, an overwhelmingly white group.

This is evident when comparing the total kicker dollars flowing to rich, white Oregonians and Oregonians of color. As a result of the 2021 kicker, white Oregonians with yearly income above half-a-million dollars — about 20,000 tax filers— together received more than $290 million in kicker rebates. Their collective total was more than the combined total kicker dollars received by the approximately 410,000 of all non-white filers in Oregon.[9]

Such an outcome is bound to worsen wealth inequality by race. For the well-off, the large, unexpected kicker rebates are not needed to make ends meet, so it’s likely that a significant portion of their kicker dollars are simply increase their investment portfolios or other assets. And because this well-off group is disproportionately white, the kicker likely exacerbates wealth inequality by race.

But, to be clear, most white Oregonians also do not fare well under current policy. The kicker that Oregonians claimed in their 2021 tax returns averaged about $850 per tax filer.[10] But because kicker dollars mainly flow to those at the top, most Oregonians — including most white Oregonians — received a kicker that was less than the average.

Transforming the current kicker to the Working Families Kicker would be good for Black, brown and white Oregonians

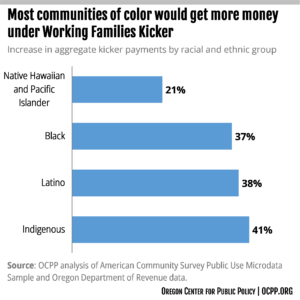

One way of making the kicker work better for Oregonians of all races is to change it to the Working Families Kicker. The Working Families Kicker would change the formula by which the kicker is distributed so that every tax filer receives the same amount. In other words, all tax filers would receive the average kicker.

The Working Families Kicker would represent a big improvement over the current kicker in terms of economic and racial equity. Had the Working Families Kicker been in place in 2021, for instance, the average Oregonian who identifies as Black, Latino, or American Indian and Alaskan Native would all have received a tax rebate of $850 — instead of $542, $519, and $512, respectively.[11] Most Black and brown Oregonians would have seen even bigger increases than that, given that the average skews upward due to high levels of income inequality. Reformed into the Working Families Kicker, the kicker rebate would become a policy that makes headway against, rather than deepens, racial economic inequality.

Another way of looking at the impact of the Working Families Kicker on racial equity is to consider how communities of color would fare as a group. Had the Working Families Kicker — an equal kicker to each Oregon tax filer — been in place in 2021, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander families would have, together received 21 percent more in kicker dollars. The gains would have been even higher for other communities of color: 37 percent for Black Oregonians, 38 percent for Latino Oregonians and 41 percent for Indigenous Oregonians. Out of the $1.6 billion total kicker payments sent out in 2021, nearly $100 million more would have flowed to people in those communities.[12]

Most white Oregonians would also fare better under the Working Families Kicker. Under the current kicker, most white Oregonians receive less than the average kicker. Again, this is due to the fact that so much of the kicker flows to the richest Oregonians. For low- and middle-income white Oregonians, the Working Families Kicker would represent a big improvement over current policy.

In sum, the Working Families Kicker would advance racial equity, while also providing larger kicker rebates to most white Oregonians. It would fix the current kicker’s inequities and benefit all Oregonians, be they Black, brown, or white.

Endnotes

[1] Daniel Hauser and Juan Carlos Ordóñez, The Kicker Fails Oregonians, Oregon Center for Public Policy, May 20, 2019.

[2] Oregon Kicker: What’s Your Cut? Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. March 1, 2023.

[3] The Oregon Center for Public Policy developed this method for analyzing the racial composition of the kicker. The demographic distribution of Oregon’s kicker was conducted by combining racial and ethnic data from the U.S. Census’ 2016-2020 American Community Survey Public Use Microdata Sample (PUMS) with data on actual 2021 tax year kicker payments from the Oregon Department of Revenue (DOR). The DOR data includes total kicker rebates and total filers for 61 income bins of full-year residents. The racial and ethnic composition of each of those income groups was calculated from the PUMS data and then the kicker for each group was distributed based upon that data to arrive at a total kicker for each racial and ethnic group in each income bin.

[4] While this analysis shows the Asian community in Oregon receiving an aggregate kicker larger than their share of filers, there is tremendous economic disparity within the Asian community in Oregon. For example, analysis by the Oregon Center for Public Policy in the Data for the People workbook finds that Asian Indian Oregonians have one of the lowest levels of economic insecurity in Oregon, while Hmong, Vietnamese, and other Asian communities have among the highest levels of economic insecurity. Unfortunately, this analysis was unable to delve deeper into the variation in kicker payments for Asian Oregonians because of sample size limitations.

[5] In the context of extreme inequality, as is the case currently, the average is often a less-than-ideal measure, as illustrated by the joke about Bill Gates walking into a bar. All of a sudden, the average patron in the bar is a billionaire. But the wealth of the median patron — the person in the middle — has changed little if at all.

[6] September 2021 Oregon Economic and Revenue Forecast. Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. Page 5.

[7] See Richard Rothstein, The Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (Liverlight: 2017); David Reiss, The Federal Housing Administration and African-American Homeownership, Journal of Affordable Housing, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2017. Jonathan Kaplan and Andrew Valls, Housing Discrimination as a Basis for Black Reparations, Public Affairs Quarterly, Vol. 21, No. 3, July 2007, at 261-63; Tracy Jan, “Redlining was banned 50 years ago. It’s still hurting minorities today.” The Washington Post, March 28, 2018; Dee Lane, “Major lenders aid decline of NE Portland,” The Oregonian, September 10, 1990; Kai Wright, “Wells Fargo Settles for $175M Over Steering Blacks and Latinos to Subprime Loans,” Colorlines, July 12, 2012; “OCPP Finds Racial Pattern in Oregon’s Subprime Lending,” Oregon Center for Public Policy, January 31, 2008.

[8] Data for the People. Oregon Center for Public Policy. December, 2022.

[9] Oregon Center for Public Policy analysis conducted using the methodology explained in endnote 3.

[10] Oregon Center for Public Policy analysis conducted using the methodology explained in endnote 3.

[11] Oregon Center for Public Policy analysis conducted using the methodology explained in endnote 3.

[12] Oregon Center for Public Policy analysis conducted using the methodology explained in endnote 3.