Read this fact sheet as a PDF: Poverty Despite Work is the Rule, Not the Exception

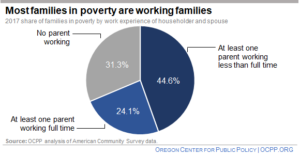

Most Oregon families living in poverty are working families, meaning they have at least one parent who works. Even families with at least one full-time worker can have a difficult time rising above the federal poverty line.[1]

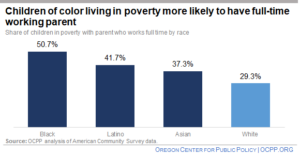

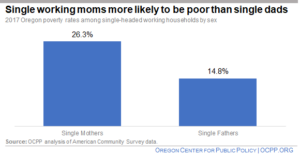

Poverty despite work weighs more heavily on some Oregonians. Children of color living in poverty, for example, are more likely to have a parent working full time than their white peers. And single, working mothers are more likely to live in poverty than single, working fathers.

Most families in poverty are working families. In 2017, the year with most recent data, 68.7 percent of poor families had at least one parent in the household who worked. Some families (24.1 percent) had at least one parent who worked full time. Others (44.6 percent) had at least one parent working part time.[2]

In total numbers, nearly 160,000 Oregonians in working households lived below the poverty line, including nearly 100,000 children. That was about the same as the number of people living in Salem, Oregon’s third largest city.

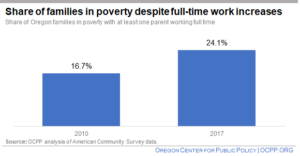

Increasingly, even full-time work is not enough to pull a family out of poverty. With the end of the Great Recession in 2009, Oregon began a robust economic recovery. And yet, poor families in Oregon were more likely to have a full-time worker in their household in 2017 than they were in 2010, the first full year of economic recovery.[3] In 2017, nearly one in every four (24.1 percent) Oregon families living in poverty had at least one parent who worked full time. That was about 44 percent higher than 2010, when 16.7 percent of poor Oregon families had at least one full-time worker in the household.

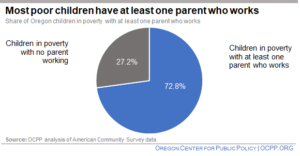

In 2017, about three of every four poor Oregon children (72.8 percent) had at least one parent who worked. Poverty, regardless of a parent’s employment status, can harm a child’s development, particularly in the early years. Research shows that the stress caused by poverty during childhood can impact a child’s cognitive development, their physical health, and their earnings as an adult.[4]

Children of color living in poverty are more likely to have a parent who works full time. In 2017, about half (50.1 percent) of all black children in poverty in Oregon had a parent who worked full time. Nearly 42 percent of Latino children and 37.3 percent of Asian children in poverty also had a full-time working parent. Fewer than one of every three white children (29.3 percent) in poverty had a parent who worked full time in 2017.

Single working mothers in Oregon are more likely to be poor than single working fathers. In 2017, 26.3 percent of single mothers who worked were poor, compared to 14.8 percent of single fathers who worked. Thus, the poverty rate for single working mothers was nearly 78 percent higher than for single working fathers.

Conclusion

Poverty despite work is the rule, not the exception. Most Oregon families living below the poverty line have at least one parent who works — often a parent working full time.

[1] This analysis uses 2017 American Community Survey (ACS) Public Use Micro Sample (PUMS) microdata. The analysis focuses on Oregon households living in poverty with a related child. The ACS categorizes work experience as “full time work in the past 12 months,” “less than full time work in the past 12 months,” and “did not work in the past 12 months.” Less than full time includes short-term and seasonal work. For example, a person who worked 40 hours per week for 10 weeks only during the winter holiday season in a retail position would be considered to have worked less than full time by the ACS. This analysis looks at the share of households in poverty with children where at least the head of household or the head’s spouse had some work experience in the 12 months prior to the survey response. While a person who worked “less than full time” could also be considered long-term unemployed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), which defines long-term unemployment as joblessness for 27 weeks or more and actively looking for work during that time, that person is still correctly counted by the ACS as having worked less than full time during the past year. Similarly, a person who “did not work in the past 12 months” under the ACS survey might not be considered “long term unemployed” under the BLS survey if the person was not actively seeking work. One is a survey of who has been working and the other is a survey of who has been unemployed; they are not meant to be mutually exclusive. Unless otherwise noted, all data in this fact sheet comes from OCPP analysis of American Community Survey data.

[2] While this paper focuses on families in poverty that have at least one parent who works, there are families in poverty that do not have a working parent. It’s important to recognize that some poor families face significant barriers to work, such as physical or mental health problems, children’s health issues, domestic violence, and lack of affordable child care. For a discussion of barriers to employment see Heidi Goldberg, <a href= http://www.cbpp.org/research/improving-tanf-program-outcomes-for-families-with-barriers-to-employment.

Improving TANF Program Outcomes for Families with Barriers to Employment, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, January 22, 2002.

[3] The Great Recession officially ended in June 2009.

[4] From Best Practices to Breakthrough Impacts: A Science Based Approach to Building a More Promising Future for Young Children and Families, Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University, May 2016.