The recession triggered by the COVID-19 crisis has hammered Oregon’s undocumented workers — workers who more likely than not perform work deemed essential during the pandemic. Their service has meant higher rates of personal and family infection and reduced income. At the same time, undocumented workers in non-essential roles have suffered a disproportionate share of job losses. All have endured the ravages of the pandemic and the recession without the substantial income supports the federal government has provided to most other workers.

It is incumbent upon the Oregon legislature to add resources to the Oregon Worker Relief Fund to better protect workers excluded from federal pandemic financial assistance.

The pandemic hit undocumented Oregon workers hard

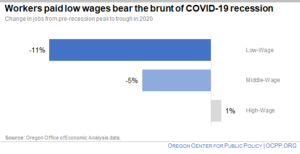

Undocumented workers have disproportionately suffered from a job market battered by the pandemic. Although unemployment data does not specifically track the immigration status of workers, other sources reveal their predicament. The COVID-19 recession hit low-paid workers harder than higher-paid workers, a group that includes much of Oregon’s undocumented workforce.[1] Oregon is home to 74,000 undocumented workers, three of every four of whom serve industries where the median wage of the jobs they fill is less than $14 per hour.[2] This is far below the overall median wage in the state of about $19.50 per hour.[3] More than one of every 10 low-wage jobs in Oregon — those paying less than $17 per hour — disappeared during the recession.[4] This is twice the loss rate for middle-wage jobs, and stands in painful contrast to gains made among high-wage jobs over the period.[5]

Further, some industries employing large numbers of undocumented workers have bled jobs. For instance, the leisure and hospitality industry in Oregon employs one in five undocumented workers. Oregon’s hotels, motels, and restaurants shed a quarter of their workforce in 2020.[6]

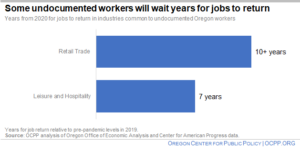

Some industries ravished by the recession and relying on undocumented workers will take years to recover. For example, hospitality industry officials estimate Oregon experienced a net loss of 600 to 800 restaurants in 2020 — establishments that closed permanently.[7] The leisure and hospitality industry is not expected to recover the jobs lost until 2027. Worse still, it will take more than 10 years for the retail industry, employing nearly one in 10 Oregon undocumented workers, to recover jobs that vanished during the pandemic.[8]

Job losses translate to lost income. This is especially true for undocumented workers, who are excluded from unemployment insurance, the wage replacement program available to many other Oregonians.

Even essential workers have lost income

Three of every four undocumented workers fill essential roles in Oregon’s critical infrastructure, as defined by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. For comparison, less than half of Oregon workers overall meet the definition of essential.[9] In a very real sense undocumented workers make daily life possible for Oregonians.

A case in point is agricultural work — an occupation deemed essential. Agricultural workers harvest, process, and deliver the food Oregonians consume. About one-third of Oregon agricultural workers are undocumented.[10]

Despite their essential role, many farmworkers have faced economic hardship over the past year. A survey of Oregon farmworkers conducted in 2020 found that most of those surveyed experienced significant loss of work and income during the pandemic.[11] Over 75 percent reported losing weeks or months of work due to their workplace shutting down, being exposed to the virus and needing to quarantine, caring for someone who got sick, or attending to children during school closures. Many were unaware of paid sick leave benefits. Some workers saw workplace changes such as lower piece rates, fewer hours of work, and loss of overtime opportunities that meant lower take-home pay.[12] Most farmworkers losing income experienced significant economic hardship, struggling to pay for basics such as food, housing, and utilities.[13]

COVID-19 has taken a bigger toll on Oregon farmworkers than the population as a whole. Agricultural worksites in Oregon have been hotspots for outbreaks.[14] About one-fifth of farmworkers surveyed in 2020 said someone in their household had contracted the virus, with nine percent of them reporting the infection had ended in death.[15] This indicates a much higher mortality rate than Oregon’s overall mortality rate of 1 percent. The death of a farmworker means the loss of income to a household, among other tragic impacts.

Farmworkers are not the only essential workers experiencing income loss. Food packing, an essential occupation employing many undocumented workers, has fostered the spread of COVID-19.[16] Workplace outbreaks can spell economic hardship for workers who fall ill and must leave work to recover, or when worksites temporarily shut down for disinfection.[17]

The Oregon Worker Relief Fund, serving undocumented workers facing hardship during the COVID-19 recession, reports that most of its grantees work in essential roles ranging from agriculture, food service, janitorial services, and childcare.[18] Nearly all of the 11,000 recipients of a similar fund for undocumented workers sickened by COVID-19 and needing resources to quarantine were essential workers in the agriculture and food processing industries.[19]

Undocumented workers are excluded from federal pandemic relief

Unlike undocumented workers, most other workers who have lost a job or income during the pandemic have been eligible for federal relief. Congress nearly doubled the amount of unemployment insurance benefits going to unemployed workers, while extending this protection to categories of workers previously excluded, such as gig workers. The federal government also provided three separate “economic impact payments” to most U.S. residents.

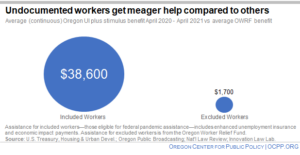

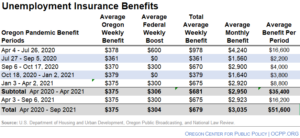

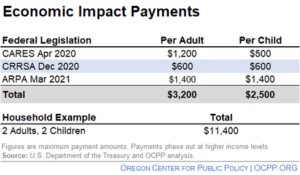

While not providing complete wage replacement for every affected person, for many workers the levels of support have been enough to forestall the worst of hardships. The average unemployment insurance benefit received by laid-off Oregon workers in the first 12 months of the pandemic was $35,000. The economic impact payments total $3,200 for an adult and $2,500 for each child. A worker continuously eligible for these federal benefits received an average of $38,600 from April 2020 to April 2021. (See Appendix A for a summary of unemployment insurance payments in Oregon and Appendix B for economic impact payments). Congress, however, shut out undocumented workers from these income supports. For Oregon’s undocumented workers, relief has come solely from a modest, single payment from the Oregon Worker Relief Fund.

The Oregon Worker Relief Fund is a lifeline but fills a fraction of need

In the summer of 2020, the Oregon legislature responded to the lack of federal relief for undocumented workers by allocating resources to a new Oregon Worker Relief Fund. The purpose of the fund is to provide a financial lifeline for households shut out of federal pandemic economic assistance. As of May 2021, the Oregon Worker Relief Fund provided $48 million in direct cash support to nearly 28,000 Oregonians ineligible for federal relief.[20] The fund channeled pandemic assistance to nearly every county in the state. Grant amounts averaged $1,700 — a modest amount compared to federal pandemic assistance. This amount has enabled families to pay rent for a month or two or to temporarily cover other basic needs.[21] Although the fund has been a lifesaver for some families, it lacks the resources to enable the kind of on-going wage-replacement security for households during an economic downturn that unemployment insurance benefits can.

The Oregon legislature can do more to protect Oregon’s undocumented workers by appropriating additional resources to the Oregon Worker Relief Fund.

Conclusion

Most undocumented workers perform essential work — the kind of work that makes daily life possible for other Oregonians. Yet, undocumented workers have suffered disproportionately from the recession triggered by the coronavirus crisis, while being excluded from the kinds of economic supports available to other workers. In the absence of congressional support, the Oregon legislature should step up to provide additional resources through the Oregon Worker Relief Fund to protect Oregon’s undocumented workers facing on-going hardship.

Appendix A

Appendix B

[1] Oregon Should Assist Laid-off Immigrant Workers Excluded from Federal Aid OCPP, April 20, 2020.

[2] Ibid. OCPP analysis of data from the Migration Policy Institute, Pew Research Center, and Oregon Employment Department. For a list of the industries and occupations Oregon undocumented workers hold and occupation median wages, see Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Joshua Lehner, COVID-19 and Job Polarization, Oregon Office of Economic Analysis, April 1, 2021.

[5] Ibid. Wage groups are based on median wages by occupation. Middle-wage jobs pay between $37,000 and $55,000 annually. High wage jobs pay above $64,000.

[6] OCPP analysis of Oregon Employment Department data.

[7] For comparison, restaurant establishments notched a net gain of 300 in 2019 and a net loss of 200 in 2018. “More than 1,000 Oregon restaurants have closed since 2020, group estimates,” Portland Business Journal, April 13, 2021.

[8] OCPP analysis of data from the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis and Migration Policy Institute. See Oregon Economic and Revenue Forecast, May 2021.

[9] Undocumented Oregon essential workers from OCPP analysis of data from the Center for American Progress. See Protecting Undocumented Workers on the Pandemic’s Front Lines, Center for American Progress, December 2, 2020. Data on Oregon essential workers from U.S. States with the Most Essential Workers, United Way of the National Capital Area.

[10] Op. Cit. Oregon Should Assist Laid-off Immigrant Workers Excluded from Federal Aid, OCPP, April 20, 2020. Also, Guidance on the Essential Critical Infrastructure Workforce: Ensuring Community and National Resilience In COVID19 Response, Version 4.0, August 18, 2020.

[11] Oregon COVID-19 Farmworker Study Preliminary Data Brief, September 21, 2020, p. 8.

[12] Ibid. p. 9.

[13] Ibid. p. 10.

[14] COVID-19 Weekly Outbreak Report, Oregon Health Authority, May 26, 2021, p. 44.

[15] Op. Cit. Oregon COVID-19 Farmworker Study Preliminary Data Brief, September 21, 2020, p. 11.

[16] Op. Cit. COVID-19 Weekly Outbreak Report, Oregon Health Authority, May 26, 2021, p. 44. Also, Op. Cit., Guidance on the Essential Critical Infrastructure Workforce: Ensuring Community and National Resilience in COVID19 Response, Version 4.0, August 18, 2020.

[17] Food processing firms can be required by state or local health officials to temporarily close for cleaning and disinfection to stop further spread of the virus. Food Processing Response Toolkit; Make a Plan for COVID-19 Mitigation in the Workplace, Oregon Department of Agriculture; Oregon Health Authority; Oregon OSHA, May 2020.

[18] Stephen W. Manning, Stephanie Powers, Narrowing the Gap, A report from the Oregon Worker Relief Coalition after a year of pandemic, May 2021.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Data Snapshot, Oregon Worker Relief Fund, May 31, 2021.

[21] Op. Cit. Stephen W. Manning, Stephanie Powers, Narrowing the Gap, A report from the Oregon Worker Relief Coalition after a year of pandemic, May 2021.