Read this report as a PDF: Oregon Lags in Fighting Food Insecurity

Unlike most other states, Oregon has made little progress in recent years in reducing food insecurity, despite a strengthening economy and rising employment.

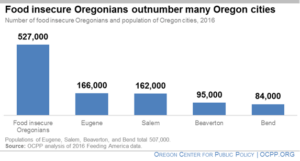

The most recent data shows that more than 527,000 Oregonians did not know where their next meal was coming from or went hungry.[1] That is more than the combined populations of many of Oregon’s largest cities.

The human cost of food insecurity is profound. Food insecurity fundamentally undermines physical and mental health. It particularly harms children, who additionally suffer greater rates of birth defects, developmental delays, and lower educational outcomes.[2]

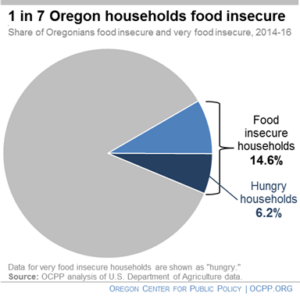

More than one in seven (14.6 percent) of Oregon households were “food insecure” during the three-year period of 2014-16.[3] Those families found it hard to put food on the table, often not knowing where their next meal would come from.

For some of these families, food insecurity was so severe that it qualified as “hunger.” These families skipped meals or ate too little because they were not able to obtain enough food they could afford.

Over the 2014-16 period, 6.2 percent of Oregon households experienced hunger.

All told, more than a half a million Oregonians — more than 527,000 — experienced food insecurity in 2016.[4] For context, that is about the same number of Oregonians who lived in the cities of Eugene, Salem, Beaverton, and Bend combined that year.

Many of those suffering from food insecurity are children. In 2016, nearly 174,000 Oregon children were food insecure, more than the number of people living in Eugene, Oregon’s second largest city.

Oregon is one of fifteen states where food insecurity is higher than the national average. During the 2014-16 period, food insecurity in Oregon ranked 14th worst among states and the District of Columbia. Oregon fared worse when it came to hunger, ranking 12th highest in the country.[5]

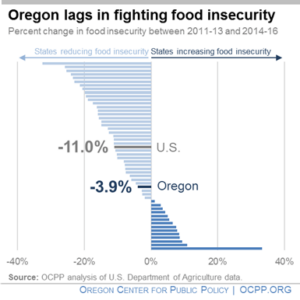

In recent years, Oregon has made little, if any, progress against food insecurity.

Comparing the most recent period of available data (2014-16), to the prior period (2011-13), food insecurity in the state was essentially unchanged, falling by 3.9 percent, a statistically insignificant amount.

Compared to the nation as a whole, Oregon measures poorly in reducing food insecurity. Over the same period, food insecurity fell by 11 percent nationally.[6]

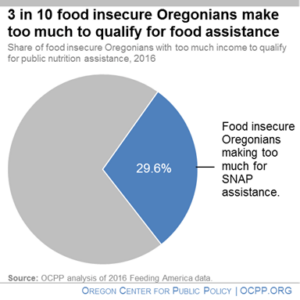

In 2016, three out of 10 Oregonians struggling with food security lived well above the poverty line, with income high enough that they were not eligible for public nutrition assistance, including from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP).[7] Oregon’s income limit for SNAP is 85 percent above the federal poverty line.

This indicates that some Oregonians employed full time and earning more than Oregon’s minimum wage are having a hard time putting food on the table.[8]

Conclusion

Despite a growing economy, many Oregon households, including many with children, struggle to put food on the table. Oregon has made little progress since the end of the Great Recession to reduce the prevalence of food insecurity. The situation could worsen , Food Research Action Center, December 2017.if Congress cuts nutrition assistance and adds obstacles for many of the eligible, as the current version of the Farm Bill proposes to do.[9]

Rather than making it harder for struggling households to receive assistance, lawmakers should strengthen nutrition supports and address growing family budget pressures that crowd out resources for an adequate and stable diet.

[1] In this fact sheet, we refer to “food insecurity” as describing survey data collected by the U.S. Department of Agriculture labelled “low food security” and “very low food security.” The latter includes multiple indications of disrupted eating patterns and reduced food intake. Definitions of Food Security,Economic Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture.

[2] A summary of the extensive research on the impact of food insecurity is contained in The Impact of Poverty, Food Insecurity, and Poor Nutrition on Health and Well-Being, Food Research Action Center, December 2017.

[3] Unless otherwise noted, the figures in this fact sheet are OCPP analysis of U.S. Department of Agriculture data.

[4] OCPP analysis of data from C. Gundersen, A. Dewey, A. Crumbaugh, M. Kato and E. Engelhard, Map the Meal Gap 2018: A Report on County and Congressional District Food Insecurity and County Food Cost in the United States in 2016, Feeding America, 2018, and 2016 U.S. Census Bureau American Community Survey data.

[5] Other states with food insecurity rates (called “low food security” by USDA) above the national average during the 2014-16 period were Mississippi (worst), Louisiana, Alabama, New Mexico, Arkansas, Kentucky, Maine, Oklahoma, Indiana, North Carolina, West Virginia, Ohio, Arizona, and Texas. Other states with hunger rates (called “very low food security” by USDA) above the national average during the 2014-16 period were Louisiana (worst), Alabama, Kentucky, Maine, Mississippi, New Mexico, Arizona, Indiana, Oklahoma, Ohio, West Virginia and Michigan.

[6] The 11 percent drop in food insecurity nationally between 2011-13 and 2014-16 is a statistically significant change.

[7] These individuals had household income above 185 percent of the federal poverty level, Oregon’s eligibility limit for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program, and school lunch programs. OCPP analysis of 2016 Feeding America data.

[8] OCPP calculates that a person working full time at Oregon’s lowest minimum wage rate (non-urban) of $9.50 per hour in 2016 earned less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level for all family sizes in 2016. Therefore, we conclude that food insecure households with earned income above 185 percent of the federal poverty line — the eligibility limit for SNAP benefits — were working at a job that paid above Oregon’s minimum wage.

[9] House Agriculture Committee’s Farm Bill Would Increase Food Insecurity and Hardship, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, May 10, 2018.