The state agency tasked with investigating claims of wage theft has seen its resources erode relative to the demand for services over the years. The Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries (BOLI) has about two-thirds the investigative capacity it possessed in the mid-1990s. As the bureau’s capacity has eroded, its responsibilities have increased, following the enactment of new laws falling under BOLI’s purview. Meanwhile, the number of wage claims filed by workers with the Bureau have increased significantly in recent years.

All of this makes clear the need for the Oregon legislature to allocate more resources to BOLI.

Wage theft in Oregon is rampant

Wage theft refers to employers failing to pay employees the wages they earned. Wage theft takes many forms, including when employers pay less than the minimum wage, don’t pay time-and-a-half for overtime hours, cheat on the number of hours worked, steal tips, require workers to work “off the clock,” or make unlawful payroll deductions.[1]

Wage theft is pervasive. Because violations often go unreported, quantifying the extent of the problem is difficult. Nevertheless, available data points to a widespread problem. Focusing on just one type of wage theft, minimum wage violations, from 2010-2020 Oregon workers lost an estimated $283 million to $405 million a year due to being paid less than the minimum wage.[2] Researchers estimate that an average of 88,000 to 128,000 Oregon workers get paid less than the minimum wage every year.[3] Again, these figures only include minimum wage violations, not other forms of wage theft.

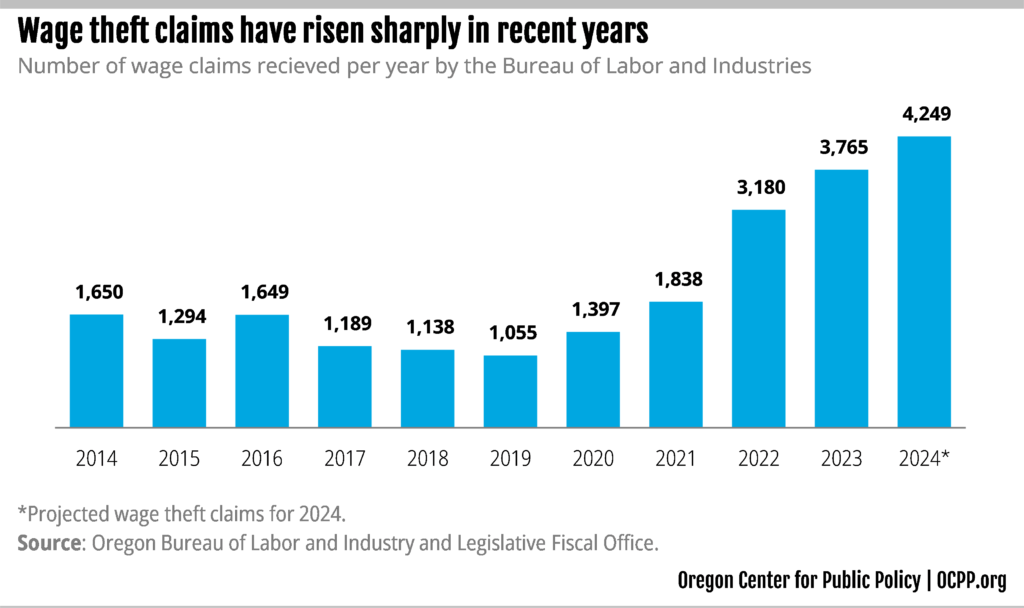

Although only a small fraction of wage theft cases are reported to BOLI, the Bureau’s Wage and Hour Division has experienced a sharp rise in wage theft claims over the past several years.[4] Between 2014 and 2021, BOLI received an average of about 1,400 annual wage theft claims. Since 2022, BOLI has averaged nearly 3,500 claims per year, more than doubling the average annual claims. And wage theft claims for 2024 are expected to set another annual record.[5]

Oregon is less able to fight wage theft now than in the past

Despite the prevalence of wage theft, the state agency tasked with protecting workers from violations of labor laws has fewer resources to combat the problem today, compared to the past.

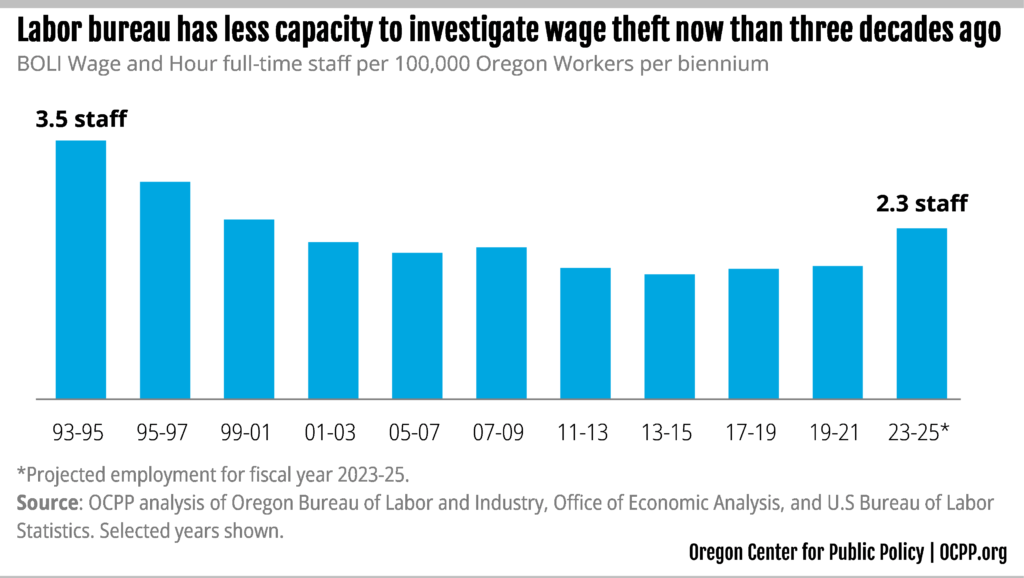

In raw numbers that do not consider the growth of Oregon’s workforce, today there are slightly fewer employees at BOLI’s Wage and Hour Division compared to three decades ago. In the 1993-1995 budget period, the time of the earliest available data, BOLI had the equivalent of 48 full-time employees helping Oregonians recover wages their boss owed them. Cuts to the agency’s budget had reduced this number to 29 full-time employees by the 2011-2013 biennia.[6] In the 2023 legislative session, however, lawmakers increased the agency’s budget, allowing BOLI to increase the number of staff focused on wage claims to 46 employees.[7]

Yet, even with the recently added capacity, BOLI’s ability to investigate and tackle wage theft remains well-below what it used to be, when measured against the size of Oregon’s workforce. The state now has about two-thirds of the capacity to investigate and enforce claims as it did 30 years ago. Specifically, in the 1993-95 budget period, BOLI had 3.5 staff persons devoted to investigating wage claims for every 100,000 Oregon workers. For the 2023-25 budget period, BOLI has just 2.3 employees working on wage claims for every 100,000 Oregon workers.[8]

Even BOLI’s 1993-95 staffing level is not the high-water mark for the state’s wage enforcement capacity. At that time, more than a decade of budget cuts had already pummeled the agency. In 1981, 30 employees were cut from the bureau, handicapping the state’s ability to investigate wage claims. In the 1991-93 biennium, BOLI let go 20 percent of the agency’s remaining staff due to budget shortfalls caused by property tax cuts embedded in Oregon’s constitution.[9]

Due to cuts to BOLI’s budget, parts of the state now lack direct support. By 1993-95, the agency had eliminated wage and hour functions in the Pendleton field office. Resource cuts caused the closure of other wage and hour field offices since then. The Bend office was shuttered during the 2001-03 biennium, and the Medford office was closed in the 2009-11 biennium.[10] Today, only offices in Portland, Salem, and Eugene remain to provide in-person assistance to workers stiffed by their boss.

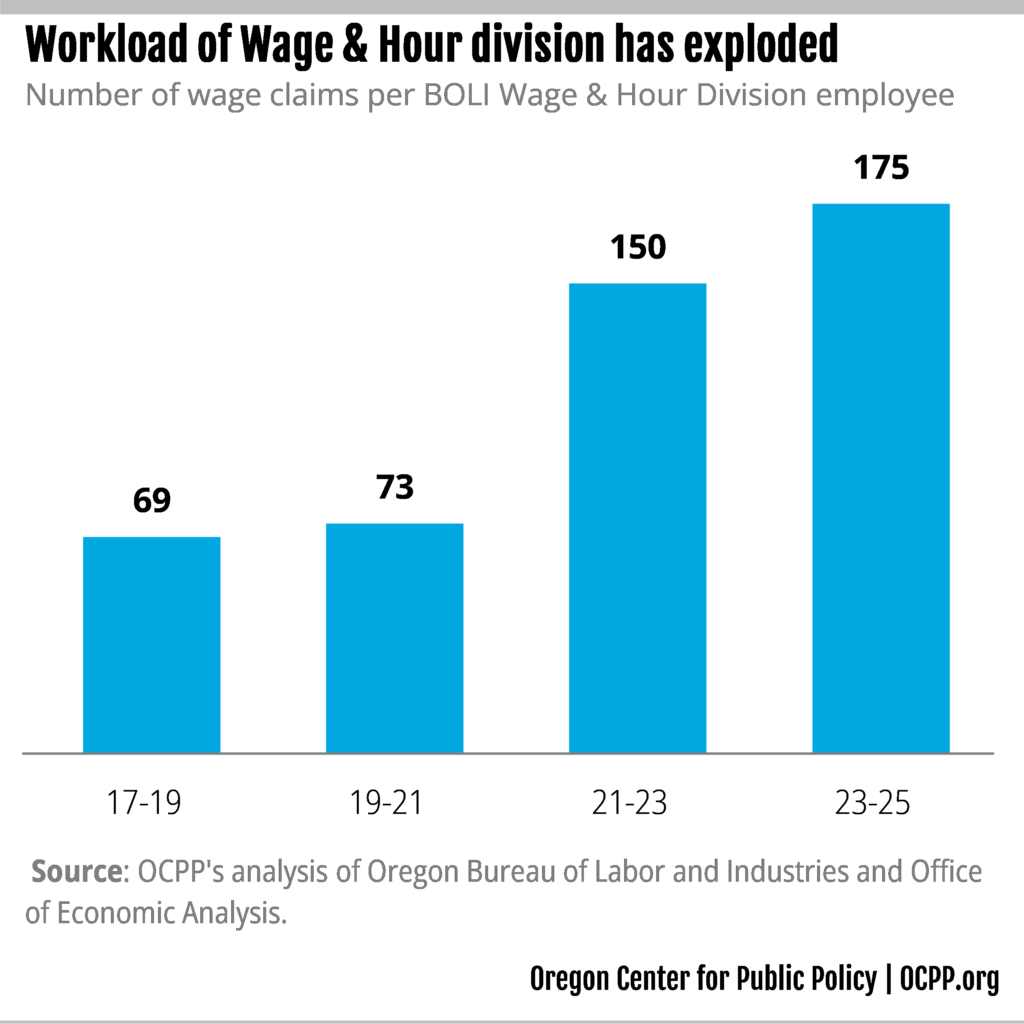

Another way to look at the challenges facing BOLI is to consider the number of wage claims per Wage and Hour Division employee. Claims per employee more than doubled between the 2017-19 biennium and the 2023-25 biennium. A particularly sharp increase occurred in the 2021-23 biennium, when the number of claims per staff surged from 73 to 150. Today, the claim workload per staff is 175 wage claims.[11]

Need for oversight and enforcement has increased

As BOLI’s staffing levels have shrunk, the state’s responsibilities have grown. In 2015, the legislature approved paid sick leave for most businesses. In 2017, it passed a pay equity law designed to rectify pay gaps for women and other groups. That year the legislature also approved a first-in-the-country law designed to protect workers from the burden and cost of unpredictable work schedules. Also, in 2017, lawmakers enacted licensure requirements for janitorial companies to prevent the misclassification of workers as independent contractors and other unfair labor practices. BOLI is responsible for enforcing each of these new laws.[12]

The agency’s responsibilities could soon grow further. In 2025, two new wage and hour laws take effect. Lawmakers in 2024 passed quota guidelines and rules for warehouse workers.[13] In 2023, the Oregon legislature also passed a law to allow hospital workers to file missed meal and rest violations with the agency as well.[14]

Fully funding BOLI becomes even more critical as workers explore creating workforce standards boards to address industry wide wages and working conditions.[15] These boards are made up of workers, employers, and state officials who have the authority to set legally binding standards for wages and workplace conditions for all workers in the industry.[16] And their effectiveness relies on BOLI’s capacity to enforce the standards they develop. For workers to have a say in regulating their workplaces, BOLI must have the necessary resources so that standards are upheld across industries.

Claims of wage theft are ignored and penalties go unpaid due to insufficient state investigative capacity

One-way Oregon’s limited funding to fight wage theft harms workers is the restrictions on the kinds of wage claim the state will investigate. For instance, BOLI does not accept a claim if:

- The claim is for commission-based wages, unless involving minimum wage violations.

- The claim involves close relatives or closely held companies, or is related only to unpaid benefits (unpaid vacation cash outs), or is an expense-related claim (unpaid reimbursements).[17]

- The claim is in excess of $15,000 and does not involve minimum wage, overtime, or prevailing wage law.[18]

The types of claims not investigated by BOLI have grown. In late 2024, the bureau announced it would stop investigating wage claims brought by workers making more than $53,000 a year, a policy implemented due to budget constraints.[19]

While the state accepts many types of wage claims, these restrictions mean some workers who are shortchanged by their boss are left to fight for their wages on their own. Limited state capacity also hampers Oregon’s ability to ensure that workers are able to collect the wages they are owed. From 2015 to 2022, 41 percent of wages and penalties ordered by BOLI against employers went unpaid.[20] The situation is particularly dire in sectors employing large numbers of low-wage and undocumented workers, such as agriculture, restaurants, and construction, where collection rates are even lower.[21]

To better protect workers, the legislature needs to invest in BOLI

The Oregon legislature can better protect workers against unscrupulous employers by providing BOLI the necessary resources to investigate and enforce wage claims.

For the 2025 – 2027 budget period, BOLI has requested an increase of nearly $22 million from the prior budget period. Among other things, this would fund a 75 percent increase in staff capacity for its Wage and Hour Division.[22] This increase would mean that BOLI would have 3.9 staff investigating wage claims for every 100,000 workers – a level slightly above what it was in the 93-95 biennium. That figure, however, does not account for the flood of wage claims filed with BOLI in recent years. In terms of the number of wage claims filed per wage and hour staff, granting the agency’s request for increased capacity would still see BOLI handling more cases per staff members than in the 2019-21 budget period — assuming that the number of wage claims filed with the agency remained constant, bucking the recent surge in the number of claims filed.

In a welcome development, Governor Kotek has proposed increasing BOLI’s budget by nearly $19 million, excluding revenue dedicated to a new semiconductor child care program that the agency would administer.[23] This would allow the agency to hire more staff, bringing its investigative capacity to 3.9 staff per 100,000 workers; improve internal operations; reduce caseloads per staff member compared to current, historically high levels; and reverse the income restriction for wage claims imposed in late 2024.[24]

The Governor’s budget, however, also falls short in key areas. The recommended budget does not include the reclassification of positions within key divisions, including the Wage and Hour division. Meeting these reclassification requests would help BOLI address ongoing retention and recruitment challenges within the agency.[25] Also, the bulk of the funding increase proposed by the governor would come from a one-time transfer from a fund administered by another agency.[26] As such, should the legislature adopt the governor’s recommendation for the 2025-27 budget, subsequent budget periods will require lawmakers to devise a more permanent solution for providing BOLI the resources it needs.

Ultimately, given that the bureau’s responsibilities have grown significantly over the past decade and the prevalence of wage theft, BOLI’s budget request and the Governor’s proposal do not go far enough to address the present need of workers, but both are steps in the right direction. Legislators will have to consider permanent sources of increased funding for BOLI in order to ensure Oregon workers’ rights are protected.

—

[1] Janet Bauer, Oregon’s Capacity to Fight Wage Theft Has Eroded, OCPP, March 28, 2019.

[2] Jake Barnes, Jenn Round, et al., Informing Strategic Enforcement Practices, Rutgers University, Updated August 2024.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Jake Barnes, Jenn Round, et al., Informing Strategic Enforcement Practices, Rutgers University, Updated August 2024.

[5] Labor Commissioner Christina Stephenson, Bureau of Labor and Industries’ Wage and Hour Division Caseload, May 29, 2024 and OCPP’s analysis of Bureau of Labor and Industries’ Wage and Hour Division Caseload.

[6] Legislative Fiscal Office, 2005-07, 2007-09 , 2009-11, 2011-13, Legislatively Adopted Budget.

[7] Legislative Fiscal Office, 2023-25 Legislatively Adopted Budget Detailed Analysis. Approximately half of these employees are investigators distributed across various units, with only ten specifically focused on wage and hour issues.

[8] In the 1993-95 budget period, BOLI had 47.76 full time workers in its Wage and Hour Division at a time Oregon had 1.3 million workers. In 2023-25 period, Oregon has 45.77 workers in its Wage and Hour Division serving 1.9 million Oregon workers.

[9] Robert Bussel, BOLI: One Hundred Years of Service to Working Oregonians, August 2024

[10] Email communication from Gerhard Taeubel, BOLI Wage and Hour administrator, to OCPP staff January 3, 2016 and Legislative Fiscal Office 2009-11 Legislatively Adopted Budget.

[11] OCPP’s analysis of Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries and Office of Economic Analysis.

[12] Bureau of Labor and Industries, 2025-27 BOLI Agency Request Budget, August 1, 2024.

[13] Oregon Legislature, House Bill 4127, 2024.

[14] Oregon Legislature, House Bill 2697, 2024.

[15] Oregon Legislature, Senate Bill 602, 2023.

[16] Oregon Center for Public Policy, Action Plan for the People, 2024.

[17] Labor Commissioner Christina Stephenson, Bureau of Labor and Industries’ Wage and Hour Division Caseload, May 29, 2024.

[18] Labor Commissioner Christina Stephenson, Bureau of Labor and Industries’ Wage and Hour Division Caseload, May 29, 2024 and Email communication from Josh Nasbe, BOLI Legislative Director, to OCPP staff, September 13, 2024. BOLI prioritizes cases that only it can enforce to ensure workers have access to a remedy. Limited legal remedies in these areas, although relatively minor, also affect how many claims BOLI can process.

[19] Labor Commissioner Christina Stephenson, Overview of Bureau of Labor and Industries’ (BOLI), September 25, 2024.

[20] Kaylee Tornay, Oregon’s Labor Bureau Failed To Collect Nearly $5 Million in Wage Theft Claims Since 2015, InvestigateWest Investigations, December 4, 2023. The 2025-27 BOLI Agency Request Budget does request additional staff for collection purposes.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bureau of Labor and Industries, 2025-27 BOLI Agency Request Budget, August 1, 2024.

[23] Oregon Legislature, House Bill 4098, 2024. Oregon Department of Administrative Services, 2025-2027 Governor’s Budget, December 2024.

[24] Oregon Department of Administrative Services, 2025-2027 Governor’s Budget, December 2024. Email communication from Josh Nasbe, BOLI Legislative Director, to OCPP staff, December 18, 2024.

[25] Email communication from Josh Nasbe, BOLI Legislative Director, to OCPP staff, February 6, 2025. Oregon Bureau of Labor and Industries, Civil Rights Division Performance Report, 2023

[26] Oregon Department of Administrative Services, 2025-2027 Governor’s Budget, December 2024.