Oregon can take an essential step to fix the widespread problem of corporate tax avoidance by enacting corporate tax transparency. Transparency means requiring corporations to make public how much they pay in Oregon income taxes, as well as enough information to understand what benefits Oregonians get from the many tax loopholes and subsidies that corporations exploit.

Oregonians pay the price when corporations shed their tax responsibilities. When corporations avoid taxes, it means either the state has fewer resources to fund schools and other essential public services, or families must pay more in taxes to make up the difference — or a combination of both.

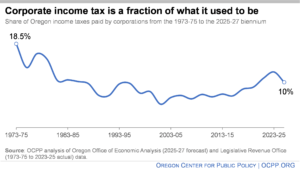

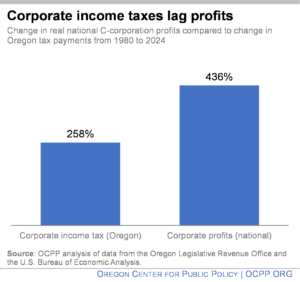

There is ample evidence that corporations have been avoiding their tax responsibilities. At a time of healthy corporate profits, the tax on those profits — the corporate income tax — has failed to keep up.[1] The share of Oregon income taxes paid by corporations has declined by more than 40 percent since the mid-1970s. Some of the decline is the result of corporations artificially shifting profits overseas to avoid paying taxes and exploiting tax loopholes and subsidies.[2]

The lack of public accountability makes it easier for corporations to avoid taxation. While it’s clear that some corporations engage in aggressive tax avoidance, the identity of those corporations is unclear, as are the precise mechanisms they use to avoid taxes. Oregon does not require corporations to make public how much they pay in income taxes or how they arrive at that figure. As such, Oregonians are in the dark as to which corporations fail to uphold their responsibilities toward the common good. Oregonians also do not know which corporations use which tax subsidies, and what Oregon gets in return for those subsidies. Ultimately, the lack of transparency enables aggressive corporate tax avoidance to go unchallenged.

That’s why the Oregon legislature should adopt the Oregon Corporate Tax Transparency Act, enumerated in the appendix. The Act would only require disclosure from large corporations that are publicly-traded, such as on a stock exchange. Enacting corporate tax transparency would increase accountability and tax fairness — a win for Oregonians.[3]

Corporate income tax has weakened, even as profits have been strong

Oregon’s corporate income tax — a tax on corporate profits — carries less weight now than it did more than four decades ago. This relative decline has happened at a time when corporate profits have been strong.

Measured as a share of all income taxes collected by the State of Oregon, the corporate income tax today is but a fraction of what it used to be. In the mid-1970’s, corporations paid 18.5 percent of all income taxes. In the current budget period (2025-2027), by contrast, corporate income taxes are only expected to make up 10 percent (about one in every 10 dollars) of all income taxes. This leaves the families who pay the personal income tax to make up the difference.

This relative decline of the corporate income tax has occurred despite an environment of strong corporate profits. Since the COVID-19 pandemic, for instance, national corporate profits as a share of national income have hovered at or near a record high of 8 percent.[4] Indeed, it is clear that the corporate income tax has failed to keep up with corporate profits. From 1980 to 2024, corporate income tax collections in Oregon increased 258 percent. Over the same period, corporate profits nationally grew 436 percent. In other words, corporate profits nationally have grown nearly twice as fast as income tax payments to the state.

Corporate tax avoidance is widespread

The weakening of the corporate income tax is in part the result of aggressive tax avoidance schemes. “Tax avoidance” refers to legal means by which corporations minimize their tax bills, as opposed to “tax evasion,” which refers to illegal means. Two common forms of tax avoidance are the shifting of profits to overseas tax havens and the use of tax loopholes and subsidies.

Rise of pass-through businesses only partiallyexplains decline of corporate income taxAnother factor driving the relative decline of the corporate income tax is the growing share of businesses that incorporate in ways that make them not subject to the corporate income tax.[5] Businesses that in the past would have incorporated as C-corporations, which pay the corporate income tax, now might incorporate as S-corporations or partnerships, which don’t pay the tax. The rise of these new corporate forms, however, only explains part of the decline. As shown above, the profits accruing to C-corporations have far outpaced the income taxes paid by C-corporations. |

The following are all well-established facts:

Corporations have lobbied for and won tax breaks

The number of tax breaks benefiting corporations have exploded over the past decades. Today, corporations can claim 73 “tax expenditures,” the official name for what are commonly referred to as “tax breaks,” “tax loopholes,” or “tax subsidies.”[6] Dozens of tax expenditures were created by the Oregon legislature, while dozens were created by Congress. Of the existing tax expenditures, 21 existed prior to 1980.[7] While some tax expenditures are well-designed to achieve an important public policy goal, many others drain resources that could be used to help Oregonians afford housing, child care, and other essentials.[8]

Some of these tax breaks are due to the efforts of corporate lobbying of Congress. Oregon’s tax code follows the federal definition of “taxable income,” so when Congress passes a new corporate tax break that alters that definition, Oregon often replicates that tax break. The only way to stop that tax break from taking effect is for the Oregon legislature to vote affirmatively to reject it, which it often fails to do. An example of this is how Oregon automatically replicated the three tax breaks included in the flawed federal tax policy known as “Opportunity Zones.”[9] The Oregon legislature was considering disconnecting from this tax break until a Republican walkout ground the 2020 session to a halt.[10]

Big corporations shift profits abroad to avoid Oregon taxes

Big corporations avoid taxes by artificially shifting profits overseas.[11] The particular mechanisms for avoiding taxes vary, but the basic strategy is the same: reduce taxable profits in the place they were actually earned and instead report them in a place that levies little or no taxes on corporate income, such as the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands.[12] Because this strategy requires having subsidiaries operating abroad, the offshoring of corporate profits is a game played exclusively by large, multinational corporations.

For instance, Oregon-based Nike, Inc., reportedly shifted $12.2 billion in earnings to offshore tax havens over a six-year period, allowing the company to shrink its effective tax rate at a time when the company saw rising sales and profits.[13] Filings with the Securities and Exchange Commission show that Nike owns dozens of subsidiaries in some of the leading offshore tax havens.[14] Other corporations with a significant presence in Oregon — Intel and Columbia Sportswear, for example — also have subsidiaries in well-known tax havens.[15]

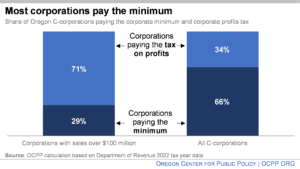

Nearly seven in 10 corporations pay the bare minimum

The most recent figures by the Oregon Department of Revenue show that 66 percent of all corporations required to pay Oregon taxes pay the minimum tax (the minimum amounts to 0.15 percent or less of their sales in Oregon).[16] This included many of the biggest corporations, 29 percent of corporations selling more than $100 million in Oregon paid the minimum.[17] Due to the lack of corporate tax transparency, lawmakers do not know how these corporations drove their taxable income into the ground, nor the identity of profitable corporations paying less than a tenth of a penny for each dollar of sales.

Oregonians need transparency to fix the problem of corporate tax avoidance

Corporations – through their lobbyists – have shaped the tax system for their benefit; corporate tax transparency is a crucial tool to fix it.

The Oregon Corporate Tax Transparency Act requires corporations to make public certain tax and financial information by filing a disclosure with the Oregon Secretary of State. The Act would apply to C-corporations that are publicly traded, meaning they are listed on a stock exchange like the New York Stock Exchange or an over-the-counter market. These corporations are already required to provide significant tax disclosures to the Security and Exchange Commission, so any cost of compliance would be minimal. This requirement explicitly excludes pass-through businesses (partnerships, limited liability corporations, S-corporations, and sole proprietorships) and C-corporations that are not publicly traded.

These businesses would disclose information such as their Oregon sales, Oregon income taxes paid, and tax breaks used.[18] Specific information outlining the tax breaks a company uses and the amount their taxes are reduced thanks to each tax break will help legislators evaluate the effectiveness of these corporate tax subsidies. (See Appendix for more information on the Oregon Corporate Tax Transparency Act.)

Corporate tax transparency would be a win for Oregonians, increasing accountability and fairness in Oregon’s tax system. Specifically, corporate tax transparency would:

- Shine a light on how corporations avoid paying taxes. While the evidence indicates that corporate tax avoidance is common, the specifics of how they each avoid taxation is often unclear. Corporate tax transparency would reveal those specifics. The information would help the public and lawmakers determine whether reforms to the corporate income tax system are needed.

- Discourage corporate tax avoidance. Corporate tax disclosure may dissuade some corporations from engaging in aggressive tax avoidance schemes, knowing that key tax information will become public. Such information would at least allow Oregon consumers to “vote with their dollars” — choosing to do business with corporations they view as supporting the common good.

- Clarify what Oregonians get in return for corporate tax breaks. Oregon has enacted many tax programs intended to create jobs or incentivize investment in the state. Corporate tax transparency would show which corporations are using which tax incentives, and how much each incentive is costing the state. This would enable policymakers to determine whether these tax incentive programs are worth their cost.

- Enable policymakers to evaluate corporate claims about the impact of proposed tax changes. When lawmakers consider changes in corporate tax policy, lobbyists for specific corporations often claim that these will increase their companies’ tax payments. Corporate tax transparency will enable policymakers to evaluate the validity of such claims.

Conclusion

Corporations have designed the tax system to their advantage. Shining a light on the corporate tax system would allow Oregonians to see which corporations pay the bare minimum in income taxes, while reporting big profits to shareholders. It will allow Oregonians to see which corporations exploit what tax loopholes and subsidies, and which might be shifting profits overseas to avoid taxes on profits earned in Oregon. In short, corporate tax transparency is essential to make the corporate income tax system work for the benefit of all Oregonians.

Appendix A: The Oregon Corporate Tax Transparency Act

Section 1: Definitions

As used in this Title, “corporation” means any entity subject to the tax imposed by Oregon Revised Statutes Chapter 317 or by Section 11 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 as amended, except that “qualified personal service corporations,” as defined in section 448 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended, shall be exempt from this Title.

As used in this Title, “doing business in this state” means owning or renting real or tangible personal property physically located in this state; having employees, agents, or representatives acting on the corporation’s behalf in this state; making sales of tangible personal property to purchasers that take possession of such property in this state, performing services for customers located in this state, performing services in this state, earning income from intangible property that has a business situs in this state, engaging in regular and systematic solicitation of sales in this state; being a partner in a partnership engaged in any of the preceding activities in this state; or being a member of a limited liability company engaged in any of the preceding activities in this state.

Section 2: Tax Disclosure Statement Required

Notwithstanding any other provision of Oregon law, the following corporations, if doing business in this state, shall file with the Secretary of State the statement described by Section 3 of this Title:

- All publicly traded corporations, including corporations traded on foreign stock exchanges; and

- All corporations fifty percent or more of the voting stock of which is owned, directly or indirectly, by a publicly-traded corporation.

Section 3: Content of Tax Disclosure Statement

The statement required by Section 2 of this Title shall be filed annually in an electronic format specified by the Secretary of State no more than 30 days following the filing of the tax return required by ORS Chapter 317 or, in the case of a corporation not required to file such a tax return, within 90 days of the filing of such corporation’s federal tax return, including such corporation’s inclusion in a federal consolidated return. The statement shall contain the following information:

- The name of the corporation and the street address of its principal executive office;

- If different from (1), the name of any corporation that owns, directly or indirectly, 50 percent or more of the voting stock of the corporation and the street address of the former corporation’s principal executive office;

- The corporation’s 4-digit North American Industry Classification System code number;

- A unique code number, assigned by the Secretary of State, to identify the corporation, which code number will remain constant from year to year;

- Except for any amount matching exactly the amount reported on the consolidated Internal Revenue Service Form 1120 as actually submitted to the Internal Revenue Service, including required schedules thereto, for any consolidated group of which any member of the unitary group is a member, the following information reported on or used in preparing the corporation’s or the unitary group’s tax return filed under the requirements of ORS Chapter 317 or, in the case of a corporation not required to file a tax return under the requirements of ORS Chapter 317, the information that would be required to be reported on or used in preparing the tax return were the corporation required to file such a return:

- Total gross income;

- Total cost-of-goods-sold claimed as a deduction from gross receipts by the unitary group of which the corporation is a member;

- The sum of the depreciation deducted and plant and equipment purchases expensed;

- Taxable income of the unitary group of which the corporation is a member prior to net operating loss deductions or apportionment;

- Calculated overall apportionment factor in the state for the corporation as calculated on the combined report;

- Total business income of the corporation apportioned to the state;

- Net operating loss deduction, if any, of the corporation apportioned to the state;

- Total non-business income of the corporation and the amount of non-business income allocated to the state;

- Total taxable income of the corporation;

- Total tax before credits;

- Tax credits claimed, each credit individually enumerated; [Note: individual enumeration might be limited to credits reducing pre-credit liability for all corporations taxable in the state collectively by more than 5-10 percent]

- Alternative minimum tax [if applicable];

- Tax due;

- Tax paid.

- The following information:

- Total deductions for services, for rent, and for royalty, interest, license fee, and similar payments for the use of intangible property paid to any affiliated entity that is not included in the unitary combined group that includes the corporation and the names and principal office addresses of the entities to which the payments were made;

- A description of the source of any nonbusiness income reported on the return and the identification of the state to which such income was reported;

- A listing of all corporations included in the unitary group that includes the corporation, their state identification numbers assigned under the provisions of this section, if applicable, and a listing of all variations in the unitary group that includes the corporation used in filing corporate income or franchise tax returns in any of the following states: Alaska, Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Rhode Island, Utah, Vermont, West Virginia, Wisconsin;

- Full-time-equivalent employment and total number of employees of the corporation in the state on the last day of the tax year for which the return is being filed and for the three previous tax years;

- Full-time-equivalent employment and total number of employees that are represented by a union contract itemized by each union contracted with;

- Median and mean wage of employees in Oregon and the number of employees making less than the statewide median wage;

- Number of employees with access to employer-provided health insurance;

- In the case of a publicly-traded corporation incorporated in the United States or the affiliate of such a publicly-traded corporation, profits before tax reported on the Securities and Exchange Commission Form 10-K for the corporation or the consolidated group of which the corporation is a member for the corporate fiscal year that contains the last day of the tax year for which the return is filed;

- Accumulated tax credit carryovers, enumerated by credit.

Section 4: Alternative Statement Option for Corporations Not Required to File Tax Return

In lieu of the statement described in Section 3, a corporation doing business in Oregon but not required to file a tax return under the requirements of ORS Chapter 317 may elect to file a statement with the Secretary of State containing the following information:

- The information specified in Section 3, items (1) through (4), inclusive;

- An explanation of why the corporation is not required to file a corporate income tax return in this state, which explanation may take the form of checking one or more possible explanations drafted by the Secretary of State;

- Identification of into which of the following ranges the corporation’s total gross receipts from sales to purchasers in this state fell in the tax year for which this statement is filed:

- Less than $10 million;

- $10 million to $50 million;

- More than $50 million to $100 million;

- More than $100 million to $250 million;

- More than $250 million.

Section 5: Supplemental Information Permitted

Any corporation submitting a statement required by this Title shall be permitted to submit supplemental information that, in its sole judgment, could facilitate proper interpretation of the information included in the statement. The mechanisms of public dissemination of the information contained in the statements described in Section 7 of this Title shall ensure that any such supplemental information be publicly available and that notification of its availability shall be made to any person seeking information contained in a statement.

Section 6: Amended Tax Disclosure Statements Required

If a corporation files an amended tax return, the corporation shall file a revised statement under this section within sixty calendar days after the amended return is filed. If a corporation’s tax liability for a tax year is changed as the result of an uncontested audit adjustment or final determination of liability by the Oregon Tax Court or Oregon Supreme Court, the corporation shall file a revised statement under this section within sixty calendar days of the final determination of liability.

Section 7: Public Access to Tax Disclosure Statements

The statements required under this Title shall be a public record. The Secretary of State shall make all information contained in the statements required under this Title for all filing corporations available to the public on an ongoing basis in the form of a searchable database accessible through the Internet. The Secretary of State shall make available and set charges that cover the cost to the state of providing copies on appropriate computer-readable media of the entire database for statements filed during each calendar year as well as hard copies of an individual annual statement for a specific corporation. No statement for any corporation for a particular tax year shall be publicly available until the first day of the third calendar year that follows the calendar year in which the particular tax year ends.

Section 8: Enforcing Compliance

The accuracy of the statements required under this Title shall be attested to in writing by the chief operating officer of the corporation and shall be subject to audit by the Oregon Department of Revenue as the agent of the Secretary of State in the course of and under the normal procedures applicable to corporate income tax return audits. The Secretary of State shall develop and implement an oversight and penalty system applicable to both the chief operating officer of the corporation and the corporation itself to ensure that corporations doing business in this state, including those not required to file a return under the requirements of ORS Chapter 317, shall provide the required attestation and disclosure statements, respectively, in a timely and accurate manner. The Secretary of State shall publish the name and penalty imposed upon any corporation subject to a penalty for failing to file the required statement or filing an inaccurate statement. The Secretary of State shall promulgate appropriate rules to implement the provisions of this Title under the rulemaking procedures described in ORS Chapter 183. Penalties equal 0.25 percent of the corporation’s gross receipts in Oregon, up to a maximum of $1 million per year.

Endnotes

[1] This paper uses corporate income tax to refer to both the corporate excise tax and corporate income tax. Unless otherwise noted, “corporations” or “corporate” refers to C-corporations.

[2] Tyler Mac Innis and Juan Carlos Ordonez, The Gaming and Decline of Oregon Corporate Taxes, Oregon Center for Public Policy, June 2016, and Daniel Hauser, Trump tax plan showers rich Oregonians with tax cuts, Oregon Center for Public Policy, October 2017.

[3] Michael Mazerov, State Corporate Tax Disclosure, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, February 2007, and Daniel Morris, The Need for Corporate Tax Transparency in Oregon, November 2017, available at.

[4] National profits data is used because data is unavailable for C-corporation profits from activity in Oregon. Figures for profits are profits after tax with inventory valuation adjustment and capital consumption from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis’ data on national income multiplied by the ratio of U.S. Internal Revenue Service data on the share of all corporate profits accruing to C-corporations in that same year. Corporate tax payment data is from the Oregon Legislative Revenue Office, 2025 Oregon Public Finance: Basic Facts. Using national profits data is an incomplete means of conveying relevant profits in Oregon, because Oregon’s corporate tax base does not perfectly match that of the nation. However, the data is still a helpful approximation to understand the trends underpinning corporate taxation.

[5] Aaron Krupkin and Adam Looney, 9 facts about pass-through businesses, Brookings Institution, May 2017.

[6] OCPP calculations based on the Oregon Department of Revenue, 2025-2027 Tax Expenditure Report. All expenditures where a corporation could or do benefit in the 2025-2027 biennium are included. Sometimes this includes expenditures that have sunset but still incur costs to the state.

[7] Ibid.

[8] The Earned Income Tax Credit is one example of a positive and helpful tax expenditure. Juan Carlos Ordóñez, Boost the EITC, improve social and economic circumstances for Oregon children, Statesman Journal, June 7, 2019.

[9] Daniel Hauser and Juan Carlos Ordonez, 4 ways ‘Opportunity Zones’ squelch real opportunity, Oregon Center for Public Policy, April 2019.

[10] House Bill 4010 (2020 session).

[11] Daniel Hauser, Oregon Can Raise $376 Million by Clamping Down on Offshore Corporate Tax Avoidance, Oregon Center for Public Policy, November 2018.

[12] The Corporate Tax Haven Index produced by the Tax Justice Network identifies the British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands as the top two corporate tax haven countries.

[13] Profits double, tax payments fall at Nike, drawing the attention of EU regulators, The Oregonian, January 12, 2019, available at.

[14] Michael Mazerov, Oregon Should Reinstate Its Tax Haven Law, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, June 2018.

[15] Ibid.

[16] OCPP analysis of data from the Oregon Department of Revenue, Oregon Corporate Excise and Income Tax: Characteristics of Corporate Taxpayers, 2019 Edition.

[17] Ibid.

[18] The Act would not include information from the new Corporate Activity Tax because the tax was developed to limit tax expenditures and relatively few currently exist.

[19] Language for the model disclosure act initially developed by Michael Mazerov, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities.